Human trafficking is rife in Peru, particularly in remote regions where poverty and lack of opportunities encourage exploitation. Children, men and women are regularly tricked by false promises and become victims of sexual exploitation, forced labour and other forms of trafficking. Prevention and awareness-raising, particularly through educational initiatives in schools, are essential to combat this scourge and protect vulnerable communities. Report (Emmanuelle Birraux, Head of Communications, Terre des Hommes Suisse / Cover photo: Carmen Barrantes).

It takes several hours from the city of Cusco to reach the municipality of Ccatcca. The road is winding and bumpy, with majestic mountains towering above. I feel lost in this immensity. One pass hides another, then another. There aren’t many settlements, but you can see a few herds of llamas and a few donkeys, reminders that men, women and families must live here. I can make them out. Without necessarily meeting them, without necessarily being able to understand the extent to which these arid, craggy, isolated expanses are their lives, their worlds.

It will take more than 4 hours to reach the municipality of Ccatcca, where Terre des Hommes Suisse and its partner Yanapanakusun are active. A large tarmac road runs through a village, deserted at this time of day. Most of the inhabitants have long since returned to their fields, agriculture being the main activity in the region. We have to get to the school high up in the village. Dirt has taken the place of tarmac and we set off along improbable paths, not without getting lost before being guided by a “motorbike taxi”, one of the locals’ preferred means of transport.

Schoolchildren from the local area are waiting for us to take part in one of their awareness-raising activities on human trafficking. I ask myself. Why talk about human trafficking in an area where everything looks so peaceful, where the snow-capped peaks in the distance seem to be watching over the souls of the people? Such tranquillity is deceptive.

Human trafficking is a reality in Peru. At national level, 1,908 victims have been reported by the Public Prosecutor’s Office, including more than 600 people in the southern corridor alone, where Ccatcca is located.

In this Andean region, women, men and children are regularly “captured” and exploited. A poor, remote region, job opportunities are rare. Many of the children at the school live with a “godfather” so that they can study. Their parents and families live in remote areas, hours away from the school. The only option for guaranteeing them an education is to entrust them to acquaintances. Leaving them alone and on their own, they are particularly vulnerable to “dream sellers”. When you’re 14 or 15, don’t you want a better life? Of a world where money would be easier? How can you refuse these tempting offers promising idyllic salaries and working conditions? It’s so easy to be fooled. And the traffickers know it. So, on the basis of false promises, fraudulent attentions and attractive job offers, many victims allow themselves to be tricked.

Carmen Barrantes, head of advocacy for Terre des Hommes Suisse in Peru, has worked extensively on the issue of trafficking in the country. She explains that trafficking is still considered a crime under ordinary law. It is all the more insidious because it is often committed by people from the same community (Quechua, for example), from the same family, or by friends. The very victims of trafficking often become perpetrators of the same acts and deceptions.

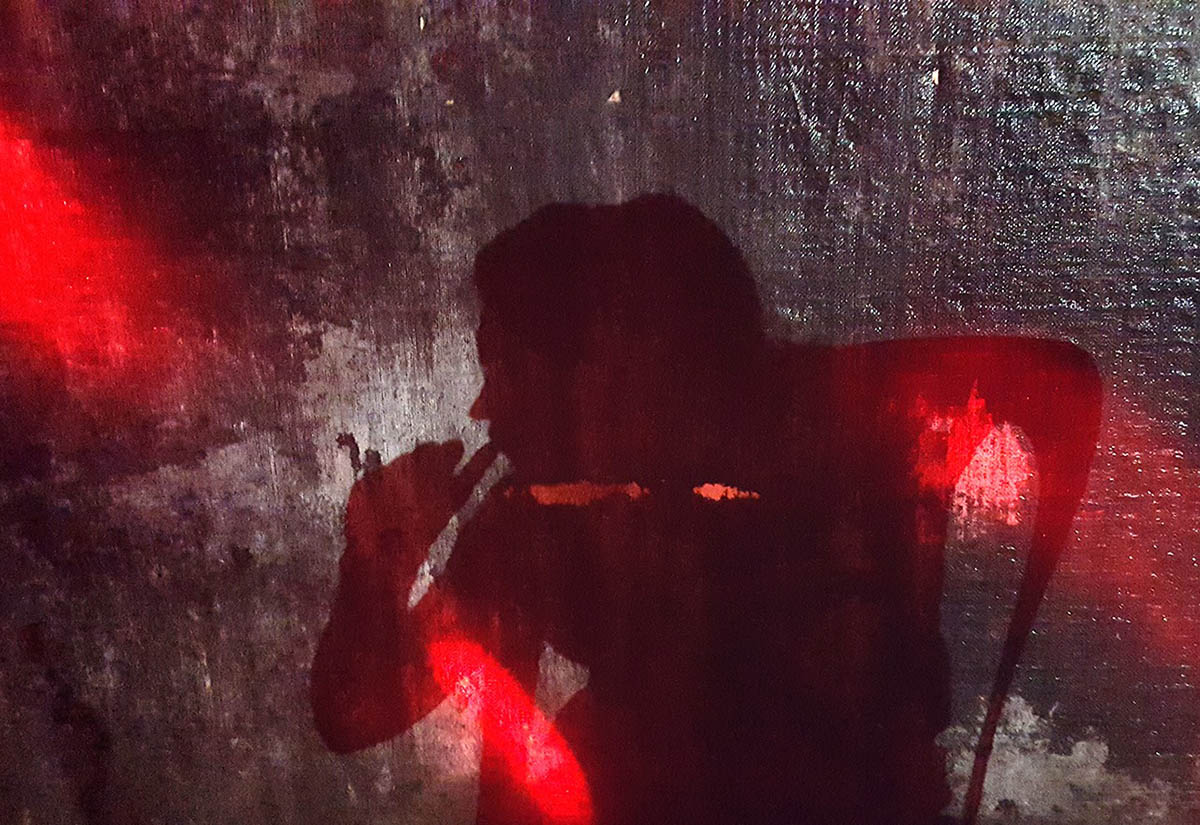

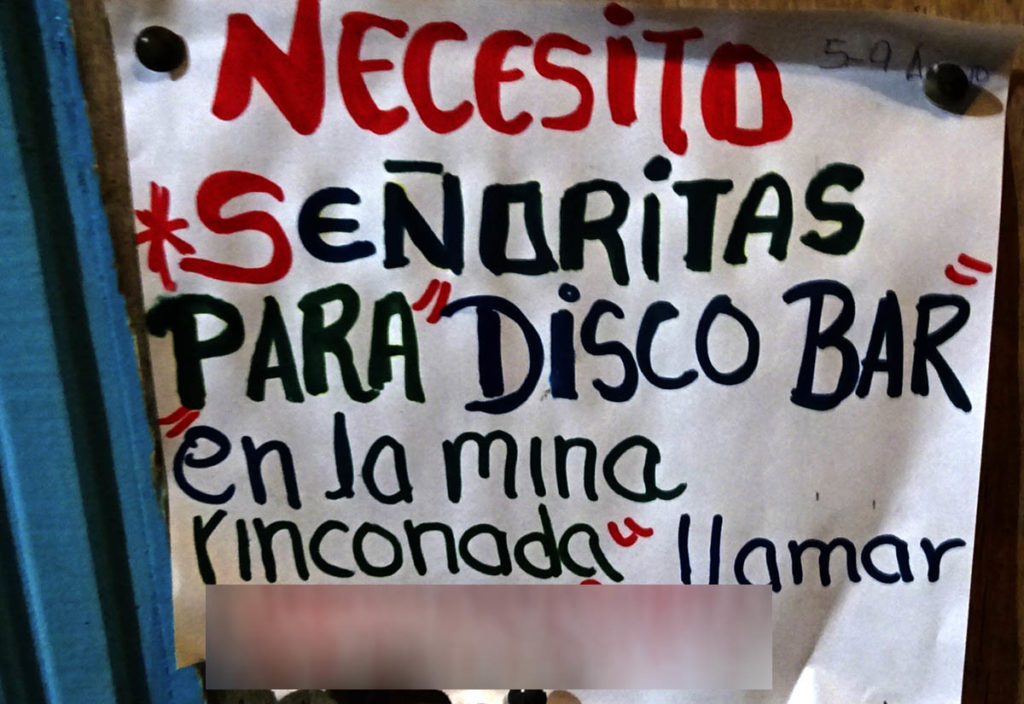

Where gold flows

All this traffic has one main destination: Madre de Dios. Situated in south-west Peru on the border with Brazil and Bolivia, in the heart of the Amazon region, this sparsely populated and isolated region is extremely rich in gold and timber. Peru is the world’s sixth largest producer of gold, and over the last few decades the country has seen extraordinary growth in small-scale gold mining. Legal and illegal mining activity is intense, at the cost of uncontrolled deforestation and irreversible environmental damage. And at the cost of an explosion in all kinds of trafficking: forced labour in the mines, sexual exploitation, domestic exploitation. Here, another form of parallel growth has developed. In some areas, along the inter-oceanic route, there are bars (prostibars) and young girls enticing the miners after a hard day’s work, a visible sign of how mining has stimulated trafficking.

The inhabitants of Ccutacca don’t talk much, testimonies are rare, out of fear, fear of reprisals, shame. Yet it’s no secret that their community is located right on the traffic route: 7 hours, 395 km on the inter-oceanic route to get from the cold zone (the Andes) to the hot zone (the Amazon). It’s a route that can easily lead to hell for these children, men and women.

Prevention as a tool in the fight against disease

Amelia tells me that her sister was 11 years old when she went to work in a house, even though she was promised that she would be able to continue her studies while helping a family with some domestic chores: “In fact, she had to do everything in this house, she didn’t go to school any more. She was treated like a slave, wasn’t paid and didn’t get enough to eat. Amelia won’t say any more. Embarrassed. As if she’d said too much.

In these areas, one of the ways of combating trafficking is through prevention. Educating, informing, talking about the mechanisms of capture, the consequences of trafficking on physical and psychological integrity, these are all essential points to be able to take concrete action against this scourge.

Today, at Ccatcaa school, a whole event is being organised by the pupils around the theme of child trafficking, and a fresco is being unveiled for the occasion: “No to trafficking! The message is clear. At each of the stands, the pupils inform their peers about the risks associated with trafficking, the forms it takes in the region where they live, and the consequences for people’s physical and psychological integrity.

He knows that prevention alone may not be enough to eradicate the problem, so difficult are the living conditions in his region and so strong can be the lure of profit, but he also knows that this step is key in the fight to protect children and young people.

Carmen Barrantes, explains that the resources made available at government level are insufficient, and the stereotypical prevention campaigns (innocent victims trapped by cruel and ruthless men) do not allow the full extent of the problem to be grasped. In all this complexity, not every effort is in vain. Terre des Hommes Suisse thus stands out as one of the first civil society institutions in Peru to work on the prevention of trafficking within the framework of a rural community programme, involving Quechua girls, adolescents and women. A stone in the building.

Take action with Terre des Hommes Suisse to protect children around the world

Every donation makes a difference to a child’s life.

Thank you for your support!